W&L Must Live by Its Mottos

W&L Must Live by Its Mottos

Washington and Lee’s presentation of history violates the goal of a liberal arts education.

(The original 1890 W&L Coat of Arms on a silk banner, left, next to the current Coat of Arms. | SOURCES: The Alumni Magazine, Washington and Lee University)

Washington and Lee University’s Coat of Arms is adorned with the timeless motto: “Non Incautus Futuri; Not Unmindful of the Future.” An admirable goal, this phrase beckons W&L, from its students to administration, to look to the times ahead in all actions, plans, and decisions.

But there is a more critical verse for a liberal arts education found at the top corner of the Coat of Arms, or Crest. Rooted in Paul’s Epistles, 1 Thessalonians 5:21, “Omnia Autem Probate” is most often translated as “Test All Things.”

Other translations, including “prove all things” and “examine all things,” universally signal the same exhortation: do not take assertions for granted. Thinking “freely” requires one not to be easily swayed by all they hear, but to, as the university's Mission Statement suggests, “critically” analyze new information.

Tragically, W&L fails to apply this rigorous analysis in its own depiction of campus life, from institutional history to its social scene, and much in between.

Our aim as participants in liberal arts education should not be to question everything around us cynically. Instead, Paul shows us that our goal should be to distinguish the good from the bad: to cherish the good, and to address the bad. We should praise the many wonderful aspects of the school we love, and meaningfully address areas where it falls short.

As an example, we should analyze how the university presents its history.

They will rightfully tell you that W&L has a history steeped in racial prejudice. Still, they won’t critically analyze the institution’s seminal role in developing the Lost Cause Mythology, nor how W&L has grown beyond that troubled period.

The administration provides a great deal of information about the Honor System, but it will not disclose the current challenges it faces or its development during Robert E. Lee’s presidency.

A campus tour will certainly pass by the president’s house, but no one will tell you it is named “Lee House” and was built for President Lee during his tenure.

They will tell you that we have a gorgeous chapel, overlooking the Colonnade. But they won’t tell you that its federally recognized name is Lee Chapel, National Historic Landmark, or that one of our namesakes, along with a Revolutionary War hero and several other influential figures, is buried beneath it.

They will tell you about the landmark Colonnade and its own beauty, but not tell you that it was primarily built through the generosity of “Jockey” John Robinson, lest they admit that a slaveowner was instrumental in saving what was then Washington College.

They will tell you that W&L are the “Generals,” but they won’t tell you about those generals: their successes or their failures. In fact, according to one anonymous student tour guide, anything to do with either of W&L’s namesakes is considered one of many “tricky situations” in university history that guides are trained to avoid at all costs.

In other words, important parts of today’s W&L are intrinsically tied to an uncomfortable past, including our namesakes and other people shunned by modern conceptions of right and wrong. Yet, this issue goes deeper than the (former) names of a couple of buildings, more than removing plaques or paintings from floors or walls.

The mission of W&L is tied to the more reviled of the two namesakes, as “Non Incautus Futuri” serves as the motto of the Lee family. The Coat of Arms is inseparably linked to both namesakes, deriving its design from the crests of the Washington and Lee families.

Even worse in the eyes of some, the W&L Coat of Arms was created for the unveiling of a now torn-down equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee on Monument Avenue in Richmond — despite the university’s website incorrectly claiming otherwise.

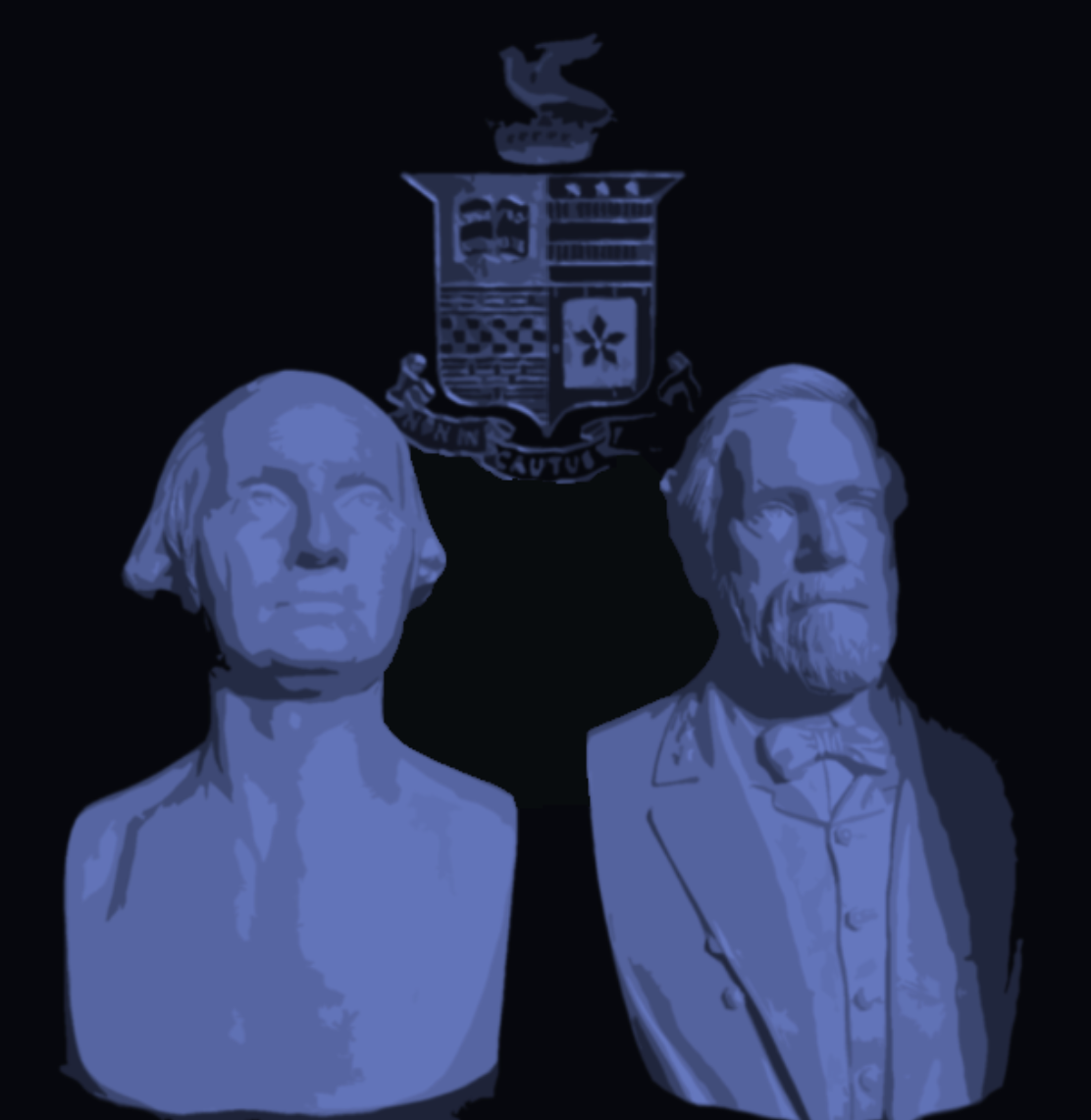

(Busts of George Washington, left, and Robert E. Lee, right, stand in front of W&L’s Coat of Arms. | SOURCE: The Spectator)

What should we do with this information? Should we throw our motto asunder? Should we change the pillars of the university, simply because they are connected to two men now condemned by some for breaching modern standards of morality?

Paul’s guidance following his exhortation to “test all things” can lead us to the answer.

The second clause of 1 Thessalonians 5:21 tells us to “hold fast what is good.” Is something “good” because it has a stainless history, or because it is admirable and fosters human flourishing? Is Paul’s message not instead to discern what is “good” in any given thing, and to separate it from any troubled parts?

W&L clearly offers a great deal to its students and graduates. In just one metric, the university ranks in the top 10 colleges in the United States for career preparation. Thus, in many ways, it should be considered “good.” Yet, clearly it is not universally so.

By both “test[ing] all things” and “hold[ing] fast what is good,” we achieve our purpose in a liberal arts education. We engage in critical inquiry not to tear down, but to find the complete, unfiltered answers to our questions, regardless of how we feel about our discovery.

To accept the university’s revision of its own history is to fail to “test all things,” compromising the truth for a feel-good story.

To abandon the core ethos of W&L because of its association with uncomfortable historical practices would fail to “hold fast to what is good,” while attempting to distance ourselves from this history.

We cannot accept the university’s sanitized history of itself, for we would not know what is true, and thereby, “what is good.” We would be “unmindful of the future,” leaving problems in the university’s fabric because we are too embarrassed even to acknowledge them, much less fix or address them.

In whitewashing its problems, the university deprives itself of an opportunity to apply its own motto on how to navigate a complicated past. Consequently, we are left with a community that is unable to find truth and has discarded the educational philosophy it calls its motto.

Will the incoming class continue to abandon our motto, or will they embrace it? Will they be mindful of the future, or unmindful of the past?