The Past, Present, and Future of Appalachian Politics

The Past, Present, and Future of Appalachian Politics

How Western Virginia and West Virginia politics shifted, and what leaders see for its future.

(Results from the 1976 United States presidential election, left, with that of the 2020 United States presidential election, right. Source: Wikipedia)

The 2024 election is set to be a doozy. The first presidential rematch in a lifetime will in all likelihood be the most expensive cycle in history. Polls have the race consistently neck and neck.

What cannot be described as nail-biters are the recent elections in the region surrounding Washington and Lee University. Voters in Western Virginia and West Virginia have turned red, a phenomenon that would have been shocking only a few decades ago.

As recently as 2019, Democrat Creigh Deeds represented Lexington and much of western Virginia in the Virginia Senate. Now, Western Virginia is ruby red in the Virginia Senate, with only a handful of Democrats in the House of Delegates, all representing urban constituencies.

West Virginia, a state whose legislature and executive positions were controlled by Democrats as recently as 2012, has only three remaining Democratic state senators, with Republicans poised to take every statewide office in this year’s elections.

To understand the shift away from the Democratic Party, which had dominated the region for decades on end, The Spectator solicited the opinions of people involved in government on both sides of the Virginia-West Virginia border.

Bill Wallace is the personification of West Virginia’s political shift. Wallace first ran for the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1984, competing repeatedly in subsequent elections. Upon filing as a Republican, according to Wallace, his friends and family said that to get elected, he should have registered as a Democrat. According to Wallace, in the 1980s the “general election was a mere formality, the Democrat primary was the real election.”

Mark D. Obenshain, a member of the Virginia Senate representing the 2nd District, described Virginia’s political past in a similar manner. According to Obenshain — a Republican — there was a large “realignment in the 50s and 60s.” But, before that, “Virginia was a one-party state” with Democratic Party rule.

So what pushed Western Virginia and West Virginia toward the Republican Party? Bill Cole says that the unchecked Democratic dominance played a part. Cole, an automotive entrepreneur, former member of the West Virginia House of Delegates and Senate, and the Republican nominee for Governor of West Virginia in 2016, believes “everyone could see the damage of having one-party rule.”

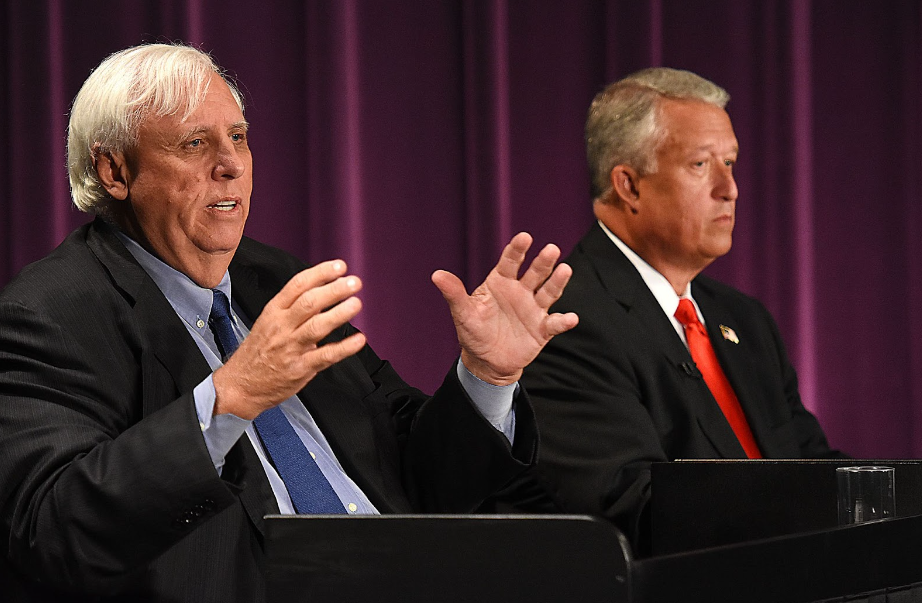

(Bill Cole, right, debates now-West Virginia Governor Jim Justice, left, prior to the 2016 West Virginia gubernatorial election. Source: West Virginia Metro News)

Republicans also frequently cited the alleged leftward shift of the Democratic Party. Cole, for instance, described the Democratic Party as having “taken such an incredibly harsh shift to the left” nationally, so much so that Cole would “guarantee their grandaddy is rolling over in his grave given their national party platform.”

Ben Anderson also noted a large generational gap in the policies of the Democratic Party. Anderson, the former Treasurer of the West Virginia Republican Party and the Chairman of the Greenbrier County Republican Party, posited that “the Democrat Party of the 1960s no longer exists.” Anderson later added that “the Democratic Party of the past is dead and I see no hope for it to come back.”

Many Republican officials contrasted the alleged leftward swing of the Democratic Party with the supposedly conservative nature of Western Virginia and West Virginia. “West Virginia overall … has been a state that has believed in strong, Christian, conservative values,” posited Vince Deeds, a Republican who represents the 10th District in the West Virginia Senate.

Frank Friedman, mayor of Lexington, Virginia, described the region as a whole by comparing it to his own city, a place he described as a “blue puddle in a sea of red in Southwest Virginia.”

Friedman, whose position is non-partisan, describes himself as “fiscally conservative and socially liberal.” He believes that the deep roots of people in rural areas can potentially inhibit a wider perspective. According to Friedman, in places where “families have been there for five generations … people know what they know.”

Friedman finds Lexington to be “more liberal because of the experiences of the people,” people who “have seen a lot of different options” after living in multiple regions of the country.

Some denied that the political shift was due to anything ingrained in the populace of the region. Sean Hornbuckle, the Minority Leader of the West Virginia House of Delegates, believes that the shift from Democratic to Republican majorities in West Virginia “boils down to resources.” “When you look at that dramatic flip … it was all about money and resources,” Hornbuckle, a Democrat, continued.

“Coal and all those issues … people started to play on that through fear-mongering.” Republicans, Hornbuckle said, had “the resources to repeat that rhetoric and the falsehoods.”

Mike Woelfel, a Democrat who represents the 5th District in the West Virginia Senate, said, “I do not think platforms really matter.” Instead, Woelfel said, “I think candidates matter … whoever has the most righteous candidate, that is how you win.”

Whether the Democratic Party will be able to recover in the region and win races will be demonstrated, in part, throughout the next two years as West Virginia and Virginia voters go to the polls.

West Virginians have been heading to the polls in early voting, with election day for primary elections on May 14. This year’s elections will include finding the replacement for retiring Democratic Senator Joe Manchin and the successor for sitting governor Jim Justice, who is a candidate for Senate.

The Commonwealth of Virginia, in 2025, will face a high-profile gubernatorial election in which sitting Republican Glenn Youngkin is term-limited. That election will coincide with pivotal House of Delegates races to determine control of a body that is split 51-49 in favor of Democrats.

So what issues face the now-dominant Republicans in West Virginia and Western Virginia?

Ben Anderson believes that Republicans face difficulty governing primarily due to their political infighting: “Republicans have a way of wanting to fight with themselves.” Anderson stressed that his fellow Republicans must find “ways to compromise with ourselves” while continuing to “remember what our identity is.”

Vince Deeds, likewise, argued that voters hope their legislators will “stay true” to their values and not compromise them for political expediency.

Many Republicans expressed concern over party-switching, arguing that it demonstrates inauthentic beliefs. Anderson openly opposes Doug Skaff, a former leader in the West Virginia Democratic Party now running as a Republican for Secretary of State of West Virginia.

Perceived elitism was another explanation for the shift in the region’s party affiliation. Anderson credited the antielitist pretensions of men like Donald Trump with a large part of Republican success in the region.

Officials had different views about the relative importance of social and economic views in courting voters.

Mark Obenshain believes that both “cultural and economic issues have driven that transition” away from Democratic strength amongst working-class voters. Obenshain tied much of the shift to the matter of “energy in Southwest Virginia,” where “coal was king, and natural gas was a close second.” This, according to Obenshain, is juxtaposed to “national Democrats that are self-proclaimed enemies of these energies that sustained entire regions.”

Bill Cole stressed the primacy of bills tackling economic issues over broader social issues. “Republicans have to continue to prove that they are ready to lead and lead effectively … and not get lost in the minutia of a lot of social issues that get us off track,” Cole said.

Democrat Larry L. Rowe, who represents the 52nd District of the West Virginia House of Delegates, also recognizes economic issues as a primary reason for the Democrat’s struggle. He believes that as long as national politics hold great sway over state and local elections, voters will not endorse the party that they considered has contributed to an exodus of jobs in the region. “You take my job away, and I won’t vote for you,” Rowe said.

His sentiments were echoed by Richie Robb. Robb believes the Democratic Party’s issues “may have been due to the decline of unions or the decline of coal, the loss of a lot of blue-collar industry,” as “West Virginia and western Virginia are at the forefront of” such job loss.

Social issues are not swiped aside, despite the bipartisan consensus that economic issues were the primary determinants of party allegiance in the region.

Ben Anderson, for instance, said that the Republican Party’s “identity is not just fiscal issues, our identity falls on social issues as well.” He feels assured that West Virginia “will always be a pro-life state, and we should be proud of that fact.”

Democrats occasionally complain about Republicans aggressively tackling social issues, especially in West Virginia. Mike Woelfel said that the West Virginia legislature “wasted day after day with cultural issues, instead of real issues.” According to Woelfel, Republicans “wanted to be culture warriors” instead of taking on “so many substantive issues that we can work on.”

Despite all the dissension, one thing unites the views of both parties: the belief that Republicans have won rural Virginia and West Virginia.

“I do not foresee Democrats being in a position to hold statewide public office… for many years to come,” said Ben Anderson.

Mike Woelfel, a Democrat, agrees with Anderson on the pessimistic future for Democrats in the region, stating that because “registration has shifted over to the Republican side,” if Democrats “don’t make quick changes … [the region] will stay Republican for the foreseeable future.”

Whether these predictions come to pass remains up to voters in both states.

(Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia’s decision to retire could signal the loss of all statewide offices in West Virginia for the Democratic Party. Source: AP Photo/Mariam Zuhaib)